150 years of caring

A look back at the Royal Children’s Hospital from the collection of the Medical History Museum.

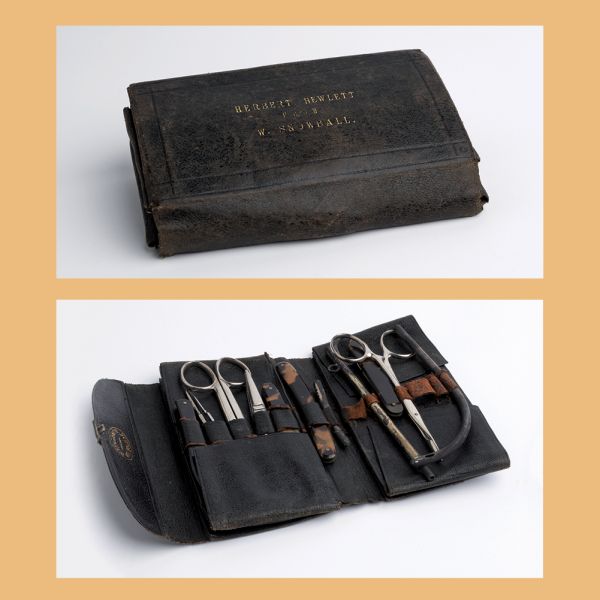

There is a remarkable object in the collection of the Medical History Museum – a pocket surgical kit in a leather case. Its significance lies in the names embossed in gold on its cover: ‘Herbert Hewlett from W. Snowball’.

In 1896, a young doctor, Herbert Maunsell Hewlett, returned home to Melbourne after graduating in Edinburgh. Under the guidance of the recognised founder of paediatrics in Australia, Dr William Snowball, Dr Hewlett established in 1897 the first radiology unit in a Melbourne public hospital at what was then known as the Children’s Hospital.

This gift is evidence of the culture of collaboration and innovation at the Children’s Hospital that is at the heart of the history of this venerable institution.

Imported/retailed by William Ford & Co. (Melbourne), Surgical instrument kit, c. 1897 – c. 1902, silver-plated and other metal, tortoiseshell, leather, velvet, paper and ink, gilt, fibre, gut; pouch 8.5 × 15.0 × 3.0 cm, inscribed Herbert Hewlett from W. Snowball. MHM02498, gift of Professor Bryan Gandevia, 1987, Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne

The publication and exhibition (online and in the Medical History Museum) The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne: 150 years of caring celebrate and commemorate the history of the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) (established in 1870), and its strong connections with the University of Melbourne (established in 1853) through teaching, research and shared alumni.

The various events organised by the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation to celebrate the 150th anniversary were spread over 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Highlights included:

- the RCH150 anniversary postage stamp release with Australia Post

- Me and UooUoo: The RCH150 Anniversary Art Trail

- Celebrate. Create. Connect. The RCH150 Aboriginal Art Project.

The present exhibition and publication are part of the University of Melbourne’s contribution to this special anniversary.

The genesis of RCH was a meeting convened in September 1870 to form a committee, whose first resolution was ‘to establish in Melbourne a hospital for children to be called the Melbourne Free Hospital for Sick Children’. This was followed by the appointment of a committee and staff. George Britton Halford, inaugural professor of anatomy, physiology and pathology at the University, was appointed as consulting surgeon. The relationship with the University of Melbourne had begun.1

The University and the hospital have since been connected through clinical teaching, practitioners, researchers and projects over RCH’s 150-year history. The exhibition and publication highlight important events in RCH’s history.

The publication is not a comprehensive chronicle, but a series of essays and vignettes written by historians and individuals drawn from the league of professionals in many fields who have cared for children at RCH in recent decades. It builds on Peter Yule’s comprehensive account, The Royal Children’s Hospital: A history of faith, science and love, published in 1999 in the lead-up to the hospital’s 130th anniversary.

From its origins as an outpatient clinic in a small house in the city in 1870, the hospital has evolved into one of the world’s leading paediatric hospitals. These following extracts from The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne: 150 years of caring showcase two key contributors.

The father of paediatrics in Australia

William Snowball, c. 1890, Johnstone O’Shannessy and Company Limited (Melbourne, active 1865–1905), carte-de-visite photograph, cardboard, ink; 16.5 × 10.9 cm. MHM00357, Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne.

It is a rare distinction to be acknowledged as the founder of a medical specialty. Yet in Australia, Dr William Snowball (1854–1902) (MB 1875, BS 1880) is known as ‘the father of paediatrics’. Born in the inner-Melbourne suburb of Carlton, Dr Snowball was to lead the country’s first public hospital established for the care of sick children.

Dr Snowball graduated from the Melbourne Medical School in 1875 and continued his studies in Britain. Pivotal to his future was experience gained at London’s Hospital for Sick Children in Great Ormond Street, established in 1852 by Dr Charles West due to the city’s high level of infant mortality. Similar circumstances were the catalyst for the founding of the Melbourne Hospital for Sick Children in 1870.

When Dr Snowball joined the hospital as a resident medical officer in 1878, it had just moved to its first major building, in Rathdowne Street, Carlton. Dr Snowball was instrumental in determining how these premises were to be used and operated.

Infectious diseases were a major problem. The hospital generally refused such cases – to avoid cross-infection – except for children who were dying. Among Dr Snowball’s initiatives were stronger infection control, less overcrowding in wards, better accommodation for nurses, and training for nurses and clinical teaching.

In 1882, he left for private paediatric practice but continued his remarkable contribution as an honorary staff member until his death at the age of 47. Indeed, he is credited with leading the hospital’s development from ‘a small parochial hospital to one of world ranking’.1

Dr Snowball was considered a great physician and gifted teacher. Contemporaries described him as a person of considerable charm and gentle manner, adored by his patients and respected by his peers. The words of Professor Harry Brookes Allen confirm Dr Snowball’s legacy as a clinician and educator:

When he first joined the staff, his colleagues were men in general practice. With much prescience, he saw that the time was coming when, with advantage to the public and themselves, they would become specialists in paediatrics, and give themselves up entirely to the study and observation of that branch of medicine.2

Dr Jacqueline Healy

1 HB Graham, Beacons on our way: Some memoirs of the Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Sydney: Australasian Medical Publishing, 1953, p. 8.

2 Quoted in B Hewitt, ‘The founder of Australian paediatrics’, in J Healy (ed.), A body of knowledge: The University of Melbourne

Making a difference for children with disabilities

Dame Annie Jean Macnamara (known as Jean, 1899-1968) (MBBS 1922, MD 1924, LLD 1966) grew up during World War I and resolved that she ‘wanted to be of use in the world’. Over her life, she realised this vision by making substantial contributions as a scientist, clinician and teacher.

As one of the earliest female doctors at the Children’s Hospital, Dame Jean Macnamara’s appointment in 1923 coincided with a poliomyelitis epidemic. In collaboration with Macfarlane Burnet, she discovered that there was more than one strain of polio virus, an early step towards the development of a vaccine. But her efforts were not confined to the laboratory; she was also responsible for the development of an efficient and comprehensive system of care for children with poliomyelitis.

In 1931, she was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship. She visited Britain and the United States, where she furthered her skills in physical treatment, adapting splints and devices to immobilise, protect and allow rehabilitation of paralysed limbs. She applied these skills not only to children with poliomyelitis, but also to those with other conditions, including cerebral palsy. While in the United States, she acquired Australia’s first artificial respirator.

For a long period (1928-51), Dame Jean Macnamara was honorary medical officer to the Yooralla Hospital School for Crippled Children, the organisation now known as Yooralla. She also introduced a range of programs to meet the diverse needs of children with disabilities and their families. In 1938, she organised a daily program at the Children’s Hospital, which included transport and provision of a midday meal. For other children, she understood that community-based services would be preferable, and pioneered the establishment of regional services.

Often working long hours without fees, she treated children with compassion and skill, listened to and counselled their families, and valued a team approach, consulting with splint-makers and physiotherapists. For her outstanding contribution to the care of polio sufferers, she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 1935. In 1966, she became the first woman to be awarded an honorary Doctorate of Laws by the University of Melbourne. Dame Jean Macnamara truly made a difference. Her legacy has paved the way for the care of children with disabilities today.1

Professor Dinah Reddihough AO

1 P Yule, The Royal Children’s Hospital: A history of faith, science and love, Sydney: Halstead Press, 1999, pp. 196-7; K Bond, ‘Dame Annie Jean Macnamara DBE: A determined clinician’, in J Healy (ed.), Strength of mind: 125 years of women in medicine, Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne, 2013, p. 70; AG Smith, ‘Macnamara, Dame Annie Jean (1899–1968)’, Australian dictionary of biography, vol. 10, Melbourne University Press, 1986.

Dr Jean Macnamara (Melbourne, 1899–1968) (designer); manufactured in Germany, Mannequins and papoose board, c. 1935, cotton and other fabric, elastic, plaster and wood; mannequin 4.7 × 32.5 × 11.8 cm; papoose board 6.3 × 37.7 × 13.8 cm. MHM02116, Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne.

This articulated wooden mannequin rests in a papoose board to illustrate deformity prevention. Designed and used by Dame Jean Macnamara to demonstrate the principles of splinting paralysed limbs to avoid deformities in poliomyelitis patients.