Improving accuracy in mental health and neuroscience, one blood test at a time

Is it depression or dementia? The brain is our most complex organ and remains one of life’s biggest mysteries. Even with state-of-the-art technology and expert clinicians, it can be difficult to differentiate between a neurodegenerative disorder like dementia, and a primary psychiatric disorder such as depression.

Even with expert clinicians it can still take years to determine whether a patient is experiencing a neurodegenerative disorder or a separate issue.

Even with expert clinicians it can still take years to determine whether a patient is experiencing a neurodegenerative disorder or a separate issue.

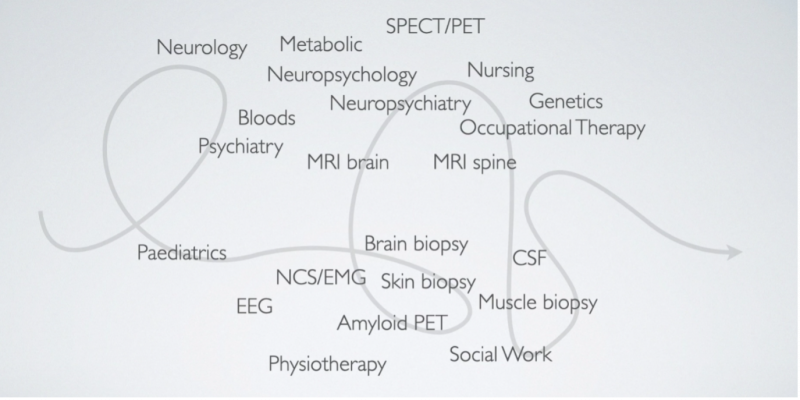

It can take an average of three years for a person to receive an accurate diagnosis of dementia and subsequent treatment. It can take much longer if you are Aboriginal or a Torres Strait Islander, from a regional area or speak English as a second language. This delay, uncertainty, misdiagnosis and repeated assessments not only impact a patient’s quality of life, but also the lives of their families, and has significant repercussions for Victoria’s entire heath care system.

Now imagine if one blood test could help clinicians make faster and more accurate diagnoses, giving doctors the confidence to tell the difference between a complex mental health and a neurological condition.

That’s where The Markers in Neuropsychiatric Disorders (MiND) study comes in.

Led by Professor Dennis Velakoulis, Professor Mark Walterfang, Clinician/Researcher Dr Dhamidhu Eratne and the Neuropsychiatry team at the Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH), the study stemmed from one key question: Can biomarkers or protein levels help to distinguish between dementia and primary psychiatric illness?

The 2019 pilot began by testing proteins in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which indicated nerve cell injury. This simple test could distinguish a broad range of complex psychiatric conditions, all of which would require different treatments, planning and management.

The study then expanded to larger cohorts, testing for a broader range of conditions. The results were promising and led to funding from NHMRC and philanthropic entities. The study has continued to grow, with the team now recruiting participants from across Australia of diverse ages, symptoms and conditions, as well as healthy people.

Collaboration remains at the forefront of The MiND study, with the RMH and the University of Melbourne building new national and international collaborations while working with the Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre to identify gaps in our understanding of complex conditions to determine appropriate treatment.

“When we started, the technology to analyse these biomarkers wasn’t available locally so we had to send our samples overseas to be analysed,” Dr Eratne said.

“Word of mouth has spread and now people all over the world are approaching us to provide input and collaborate with the MiND study.”

What sets the MiND study apart is that it scans for a broad range of conditions, recruits people from the community and primary care settings, and looks at changes in biomarkers over time. This could one day help clinicians identify a condition even before people present with any symptoms or concerns, paving the way for earlier intervention, delaying onset, and maybe even one day preventing symptoms and conditions.

Dr Eratne said: “Our hope is that one day these tests could be used before people get symptoms and, just like a GP routinely checks your cholesterol, the test could measure your risk. If it’s too high, you intervene to delay onset. This will be a dramatic step forward for the mental health system and our goal to one day, prevent onset altogether.”

The MiND team continue to make advancements in this ground-breaking field, hoping to improve the lives of millions worldwide who are diagnosed with neurological or complex mental health conditions every day.